Note

The following is a copy of an article I

originally posted on Blogger.com, September 04,

2011:

https://paultrafford.blogspot.co.uk/2011/09/siam-in-16th-and-17th-centuries.html

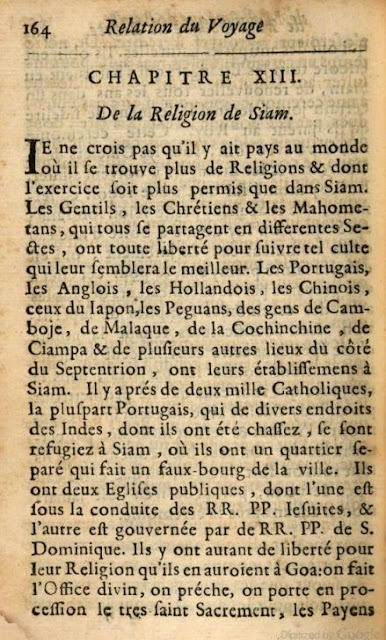

This opening paragraph comes

from Relation

du voyage de Mgr. de Béryte, vicaire apostolique du

Royaume de la Cochinchine (Account

of the Travels of The Mgr. [Bishop] of Beirut,

Vicar Apostolic for the Kingdom of

Cochinchina), compiled by Jacques de Bourges,

published in 1666 and made available as a Google

eBook.

Drawing on my schoolboy French, a translation

might be:

I do not believe that there’s a country in the

world where one finds more religions and whose

practice is more permitted than in Siam.

Gentiles, Christians, and Muslims, who are all

divided into different sects, are at complete

liberty to follow such worship as seems best to

them. The Portuguese, English, Dutch, Chinese,

Laplanders, Peguans, along with people from

Cambodia, Malacca, Cochinchina, Champa, and

several other places on the Septentrion coast,

all have established themselves in Siam. There

are nearly two thousand Catholics, the majority

Portuguese, who have come from various places in

the East Indies, from which they were driven, and

have taken refuge in Siam, where they have a

separate district making up a suburb of the

city…

Thailand’s reputation for openness goes back a

long way! Yet, I was still surprised by the

plurality of the situation described here more than

300 years ago. Quite a distinguished case of

‘multiculturalism’ (about which contemporary

discussions might suggest that it’s a recent

phenomenon!) What is not clear from this picture,

though, is whether there developed much in the way

of cultural exchange and integration among the

communities. The compartmentalising suggests each

group went its own way and the various accounts

I’ve read so far seem to confirm this and they

often relate complaints about each other and

contrary points of view, especially among the

Europeans.

I’m interested particularly in the East-West

encounter, which in this period was concentrated in

Ayutthaya, the old capital of what was then termed

‘Siam’ (which appears to have had external origins,

which I may try to explain vis-a-vis ‘Thai’ and

‘Tai’ in another post). It was missionary zeal that

drove much of the first two centuries of

expeditions and settlements – and the religious

institutions seemed often to be better informed and

coordinated than the state-sponsored trading

companies. Today the deep-rooted influence of the

West is often characterised in terms of the

material trappings of globalisation, but arguably

more persistent effects are evident in the

education system, where many schools still have a

Christian foundation and this is more my focus here

as I try to explore its origins and development in

these early accounts.

This means having to keep practising my French

language skills as most of the written accounts

relate to the experiences of the French.

Given this predominance of materials it’s difficult

to draw a non-partisan view. Among the

French records, Martin’s accounts are probably the

most valuable for the meticulous attention to

detail (recording a constant stream of news in the

manner of a ledger, even leaving blanks as

placeholders for figures that were still to be

determined). However, his background and

allegiances do colour his

interpretation. There were a few other

travellers who passed by without having

involvement, one of whom was the German naturalist

and physician, Engelbert

Kaempfer – I look forward to reading

his A Description of the

Kingdom of Siam 1690(Itineraria Asiatica:

Thailand). At least the task is made somewhat

easier by electronic publishing; in sponsoring

large scale digitisation of old texts, Google has

been providing marvellous support for this

historical research.

Among the few scholars who appear to have

studied the materials from this period in depth is

Michael Smithies, a historian. He has published

extensively and I’ve already availed myself of a

copy of his book, A Resounding Failure:

Martin and the French in Siam, 1672-93,

published by Silkworm Books. The back cover

summarises its importance: “François Martin, from

his unique viewpoint as director of the French

trading outpost at Pondichery, provides a careful

analysis of the motives of the persons involved in

the French colonizing venture.” And there were many

players in this theatre!

Prof. Smithies original studies were in French

and his teaching of French (and Indonesian) in

Papua New Guinea earned him the honour of being

received into the French Order of Academic Palms (I

don’t know the UK equivalent, but it’s a notable

decoration). In an

interview for Bulletin No. 17 Amopa 79,

2005-6, he relates his career development. In

particular, he joined the British Council in 1960

and was immediately sent “as a matter of urgency”

to Thailand as Director of English studies. He

recounts that he had to monitor the work of dozens

of teachers, and assist in teaching at different

universities in Bangkok. At that time

my mother (then Fuengsin Sarayutpitag),

recently graduated from Chulalongkorn University,

was teaching English as a foreign language at the

newly established Thonburi Technical College. She

knew a “Mr. Smithies” and I expect it was the same

man. It would be nice if this could be

confirmed.

Whilst Smithies was familiarising himself with

Thai culture (it was about 10 years later that he

started to devote himself to scholarly research in

this field), my mother was undertaking the

complementary activity of delving into Western

culture. And this is the general perspective that

I’m trying to keep in mind as I look at this

confluence, in which my mother was inextricably

involved for the rest of her life.

The Far East continues to be a source of

attraction for French missionaries, as evident

in a

trailer for a film ‘Ad Vitam, La Grande

Aventure des Missions Etrangères de Paris en Asie’.

The excerpt includes a brief historical explanation

by the archivist, Fr. Gerard Moussay, who describes

the origins of M.E.P.: in the 16th and 17th Century

the Vatican gave the kings of Spain and Portugal

the right to nominate missionaries across the

world, but with the kings becoming increasingly

ineffective in carrying this out, bishops

called Apostolic Vicars were

appointed, the first two being Mgrs. François

Pallu and Lambert de la Motte.

Regarding present day attitudes, Fr. Etcharren,

Supérieur Général of MEP, emphasizes that being a

missionary means carrying a message that’s “not

ours” and requires always humility. He offers

us another glimpse into how the early period is

viewed in a short speech he gave on a recent visit

to Thailand (see another

video), in which they celebrate 350 years in

Ayutthaya. He recounts the arrival of the

first missionaries in 1662:

Ce Lieu d’Ayutthaya a été dès le début d’abord

un lieu de prière, de contemplation et de

réflexion missionaire. Lorsque les missionnaires

sont arrivés ici, ils ont commencés par faire une

retraite et puis ensuite un synode de réflexion.

Les valeurs qui ont émergé lors de ce synode

d’Ayutthaya sont des valeurs missionaires qui

sont toujours d’actualité.

In English (again I translate):

This place in Ayutthaya was from the outset

firstly a place of prayer, contemplation and

missionary reflection. When the missionaries

arrived here, they began with a retreat followed

by a synod of reflection. The values which have

emerged from the synod of Ayutthaya are the

missionary values which are still current

[today].

This gives the impression that there has been

continual activity, perhaps suggestive of serene

and steady development, but it’s not been like that

historically because inevitably there has been a

lot of political involvement.

From the accounts of de Bourges (cited above)

and others, the Kingdom of Siam might have seemed

an opportunity ripe for successful missionary

endeavours. The French were certainly

encouraged to invest a lot in developing their

presence in the region; Martin relates in 1675

about Mgr. Pallu, Bishop of Helipolis:

This great prelate, whose probity and sanctity

Europe, Asia and America admire, had embarked in

Siam on a vessel of a private French merchant to

go to Tonkin, to devote the rest of his strength

to the conversion of the infidels. (II,13,

translated by Smithies)

There were many ‘gains’ in some parts, but

efforts were in vain in Siam (and Martin merely

echoes the uncharitable remarks, which sound like

those of a bad loser):

I also learnt from letters from Siam that the

French Missionaries made many conversions in

Tonkin and Cochinchina. Things were not the

same in Siam, although this place was like an

entrepot for the other missions and from where

they were supplied with all essentials.

This was attributed to the stupidity of the

Siamese, a brutal people to whom one could not

explain the mysteries of the Christian religion.”

(II, 86, translated by Smithies)

Even so, efforts gathered pace as we also learn

from Martin that under Louis XIV, the French were

by the mid 1680s emboldened to issue various

demands to the Siamese king, Phra Narai, including

his conversion from Buddhism to

Christianity. The bishops attempted to

win over the king through rational argumentation,

but the king simply concluded that Christianity –

alongside other religions – was basically good and

he felt no need to change his own Buddhist

affiliation.

Meanwhile, the French military presence

continued to grow until it was all too much for

some members of the Siamese court: in 1688 there

was a revolution and the French were formally

ejected under a treaty of ‘honourable

capitulation’. With a formal trade embargo then

introduced and enforced for about 150 years, there

was a lull in the nation’s engagement with the West

– we have to wait until King Rama IV before formal

ties with these nations are resumed. However,

I expect that smaller scale developments continued

and it may be interesting to find out more about

them.